Bath: North Carolina’s First Town

by Bea Latham

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian. Spring 2006.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

See also: Bath (Encyclopedia of North Carolina); Port Bath

The adage that “the grass is always greener on the other side” can in some ways be applied to the exploration of unknown lands hundreds of years ago. Were it not for the curiosity of the initial explorers or for the monarchs’ encouragement of expeditions in hopes of increasing their wealth, the whole scope of the Western world may have been “discovered” in a different time frame.

The adage that “the grass is always greener on the other side” can in some ways be applied to the exploration of unknown lands hundreds of years ago. Were it not for the curiosity of the initial explorers or for the monarchs’ encouragement of expeditions in hopes of increasing their wealth, the whole scope of the Western world may have been “discovered” in a different time frame.

We normally think of the discovery of new lands and settlement in the past tense, as we know that few unexplored areas exist in our world today. But, possibly, future generations may look at our strides in space exploration over the past fifty years in the same light. Who is to say that three hundred years from now, new colonies will not be flourishing on other planets? That may be hard for us to imagine, since those places seem so faraway, and traveling there would be neither practical nor timely. But that concept is probably no different than the prospect of our forefathers boarding ships for long,

treacherous voyages across the sea or riding in covered wagons across open prairies. Were it not for those immigrants facing the unknown, many things in our lives would be very different today.

While we might like to think of these early settlers as adventurous, the fact is that most emigrants left their homelands to escape harsh living conditions. Such changes in residence were not specific to one class of people. In fact, our Carolina settlers were a very mixed group that included well-to-do planters, laborers, religious dissenters, apprentices, and convicts. Immigrants from continental Europe often fled wars, pestilence, and famine. Some wanted to escape religious or political persecution. The Scots-Irish colonists were largely indentured servants or displaced tenant farmers. The Germans were mainly unemployed artisans or yeomen without property or livelihood. For some immigrants, any place would have been better than where they were.

Let’s explore how immigration and migration relate to eastern North Carolina and to Bath. We are familiar with early English efforts—including the 1587 one organized by Sir Walter Raleigh—to start a colony at Roanoke Island. Unfortunately, this group of about 110 settlers failed in its attempt and is better known to us as the Lost Colony. On

April 10, 1606, King James I of England chartered the Virginia Company of London to encourage colonization in the New World, in an area that then included present-day North Carolina. The first expedition sailed from London on December 20, 1606. On May 12, 1607, the three ships landed on a small island along the James River, nearly sixty miles from the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. It was there that the 104 men and boys established Jamestown in present-day Virginia as the first permanent English settlement.

This group proved more successful in its attempt to survive partly because it developed an economy dependent on the cultivation of tobacco, which could be exported to Europe. Tobacco production required intense labor, and manpower was in short supply. Many people convicted of petty crimes in England were sent to the area as indentured servants required to work for four to seven years before earning their freedom. Africans were first brought to the American colonies to work as indentured servants, but as laws changed, many became enslaved to tobacco growers. Children also became part of the labor force. It was not unusual for a family of little means to legally sign a child over to another person to learn a trade, since public education was not available to everyone, as it is today. As uncaring as this system may seem, it gave children a way to eventually support themselves in adulthood and perhaps buy land of their own.

In 1618 the Albemarle. Settlers began to move to the area that eventually became northeastern North Carolina in search of more productive and fertile soil, referred to as “good bottom land.” They found life profitable in this shore and creek area, but as word of the opportunities spread, migration occurred, the population grew, and soon it became necessary for some people to move even farther south through forests and swamps to the fertile soil associated with the Pamlico River region.

The early settlers of the Pamlico River area came from all classes of society and all walks of life. Some individuals were more accustomed to life in a new colony, since they had come south from Virginia. People arriving by ship from England and other European countries found life in the desolate region a difficult adjustment. Only a few of the early settlers had considerable wealth. Others had enough to live comfortably, but the greatest number had little more than the bare necessities. Homes were often of one or two rooms, and the floors most likely of dirt. Furniture was usually homemade and may have included only beds, a few chairs, and a table. Survival depended on work by all family members. Colonists learned skills such as weaving and farming at a young age.

The early settlers of the Pamlico River area came from all classes of society and all walks of life. Some individuals were more accustomed to life in a new colony, since they had come south from Virginia. People arriving by ship from England and other European countries found life in the desolate region a difficult adjustment. Only a few of the early settlers had considerable wealth. Others had enough to live comfortably, but the greatest number had little more than the bare necessities. Homes were often of one or two rooms, and the floors most likely of dirt. Furniture was usually homemade and may have included only beds, a few chairs, and a table. Survival depended on work by all family members. Colonists learned skills such as weaving and farming at a young age.

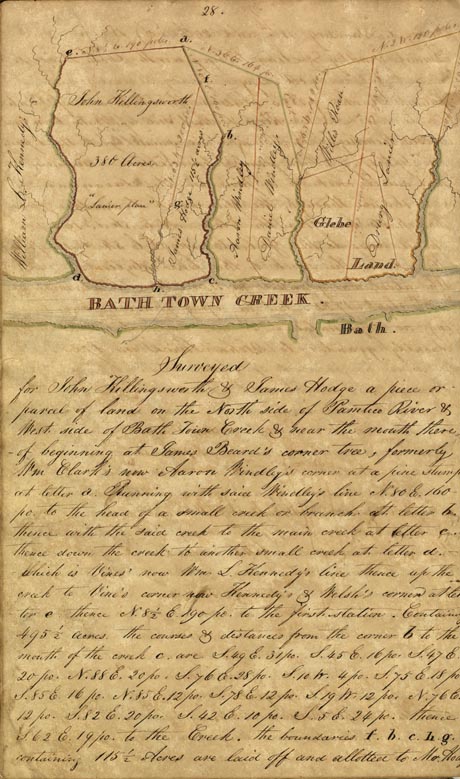

Documents show settlers scattered throughout the Pamlico River region as early as 1690. In December 1700 English explorer and botanist John Lawson began his journey from Charleston, in present-day South Carolina, northward in search of land suitable for a settlement. He ended his quest in February 1701, when he sighted the high-banked land nestled in a quiet cove just off the Pamlico River. Word spread quickly of this desirable area that offered many advantages, such as water access, plentiful game, abundant pine and cypress forests, and rich farmland. A town with seventy-one lots was surveyed and named Bath in honor of Englishman John Granville, Earl of Bath. With the ability to purchase lots, residents migrated to the new settlement from the northern areas, and to a lesser extent, from Europe. This growth led to legislation passed on March 8, 1705, that made Bath the first incorporated town in Carolina.

As the first named town, Bath quickly became an area of importance. Government officials conducted business and established their homes there. Port Bath, the first official port of North Carolina, was so named in 1715. Ships brought not only settlers but goods for those living in the area. Those ships would leave the wharves lining the shore along Bath Creek filled with the valuable tar, turpentine, and pitch—or naval stores—collected from the longleaf pine trees and sought back in the homeland.

Some of our earliest descriptions of Bath and its people can be found in letters from missionaries sent by the Church of England to deliver the word of God. In 1709 the Reverend William Gordon reported that Bath consisted “of about twelve houses” but had not built a church. He went on to write that the “Pamlico area in all probability will be the center of trade since it has the advantage of a better inlet for shipping and is surrounded with pleasant savannas for cattle.” In addition to growing numbers of English immigrants, Bath’s early settlers included French Huguenots, who began moving from Mannakin Town on the James River in 1705. Some of their surnames are still found in Bath.

Economic growth and decline have been experienced in Bath over the years because of outside forces, such as the move of county government activities to Washington, North Carolina, in 1785, and the Civil War (1861–1865). At the end of the 1800s, Bath again flourished as steam mills appeared along the waterfront. Farming and fishing were lucrative professions, and families were often quite large, as it took many hands to succeed.

These days, we tend not to categorize people as they move from place to place as immigrants or migrants, even though the definitions have not changed. Moving within a town, city, state, country, or even the world is accepted as a way of life since the ability to travel easily and quickly has advanced. But, even today, this type of movement can greatly change the face of an area. Bath as the small hometown in the early to mid-1900s is a much different place now. In that earlier time, the land and water were sources of income, and several generations often lived in the same household, resulting in the town’s population having reached 600 at times. As transportation advanced, more children began to attend college, and in seeking a more urban lifestyle, to migrate to the cities. Today, the quiet hamlet is home to about 280 residents. As our forefathers, whether fifty or 250 years ago, migrated to other areas looking for a better life, Bath’s residents today are mostly retirees who have migrated there from the quicker pace of large cities, seeking the quieter, more relaxed pace of the waterfront town—and maybe an atmosphere that matches their childhood memories.

Many aspects of Bath, like the water and the land itself, have not changed much since Lawson landed on the banks of Bath Creek in 1701, but certainly the people making up the town have changed quite often. Who knows how many times one area can fluctuate between deprivation and prosperity or population growth and decline? But the bottom line is always—the only constant thing is change.

At the time of the publication of this article, Bea Latham serves as historic interpreter at Historic Bath State Historic Site. As part of Bath’s three hundredth anniversary celebration, in 2005 she and Tricia Samford helped update a new version of Alan D. Watson’s book Bath: The First Town in North Carolina. To learn more about Bath, visit http://www.nchistoricsites.org/bath/bath.htm.

Virtual tours of Historic Bath are available on the Historic Sites Web site at: http://www.nchistoricsites.org/bath/bathvt/bathvirtualtourV.htm.

References and additional resources:

"Historic Bath." NC Historic Sites. Accessed 10/15/2010. http://www.nchistoricsites.org/bath/bath.htm

"Bath Tricentennial Digital Exhibit." Eastern North Carolina Digital History Exhibits. Accessed 10/15/2010. https://digital.lib.ecu.edu/collection/bath.aspx

Ewen, Charles R. “John Lawson’s Bath: A Subterranean Perspective.” The North Carolina Historical Review 88, no. 3 (2011): 265–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23523631.

1 January 2006 | Latham, Bea