Shortages, Substitutes, and Salt:

Food during the Civil War in North Carolina

By Thomas Vincent

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian, Spring 2007.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

Colonel Frank Parker was hungry. Parker, the leader of the Thirtieth Regiment North Carolina Troops during the Civil War, wrote to his wife in Weldon in January 1862 that “I shall await the arrival of your potatoes, sausage & c. with patience and shall welcome them with open mouths and good appetites.” Soldiers who fought in the war often did not get enough food. When they did receive food, it often was not very good. They sometimes ate the same thing day after day. The soldiers looked forward to packages from home, but often their families did not have enough to eat themselves.

Colonel Frank Parker was hungry. Parker, the leader of the Thirtieth Regiment North Carolina Troops during the Civil War, wrote to his wife in Weldon in January 1862 that “I shall await the arrival of your potatoes, sausage & c. with patience and shall welcome them with open mouths and good appetites.” Soldiers who fought in the war often did not get enough food. When they did receive food, it often was not very good. They sometimes ate the same thing day after day. The soldiers looked forward to packages from home, but often their families did not have enough to eat themselves.

North Carolinians suffered many hardships during the Civil War. About 125,000 men from the state served in the Confederate army, and others served in the Union army. The war lasted from 1861 to 1865, and soldiers were away from home for months and sometimes years. Since many of the men who joined the army were farmers, the wives and children they left behind had to do the farmwork. That meant less food to eat. People did without some things we consider common, or they found substitutes. An April 1863 article in a Greensboro newspaper, for example, explained that okra seeds could replace coffee beans, if “carefully parched and the coffee made in the usual way, when we found it almost exactly like coffee in color, very pleasantly tasted and entirely agreeable.” Mary Grierson, of Cabarrus County, in her memoir How We Lived during the Confederate War, listed wheat, rye, and sweet potatoes as substitutes for coffee. She also wrote that molasses cane “was crushed with wooden rollers by horse power and the juice boiled in wash pots . . . [and] . . . was used instead of sugar—we called it ‘long sweetening.’”

In the early days of the Civil War, people sent food and clothing to their family members in the army. As the war went on, and the men were away for longer periods, there was less to send. The Union navy blockaded Southern ports to stop ships from bringing in supplies. Agents from the Confederate government requisitioned food and livestock, taking them for the army to use. Union troops came through some areas of North Carolina and stole food and animals.

In early 1863 Mary Williams and fifty-nine other desperate women from the western part of the state asked Governor Zebulon Vance not to draft any more men from their farms into military service. The women noted that without the men they could not plant as many crops. The farmwives wrote, “Famine is staring us in the face. There is nothing so heart rending to a Mother as to have her children crying round her for bread and she have none to give them.” County sheriffs and local governments tried to provide food for soldiers’ families, but many people still went hungry. Sometimes they tried drastic measures to get food.

In the town of Salisbury in March 1863, a group of fifty to seventy-five women armed with axes and hatchets descended on the railroad depot and several stores looking for flour. The women thought that the railroad agent and the storekeepers were hoarding flour, hiding it to sell later at a higher price. When faced with the angry mob, the storekeepers gave “presents” of flour, molasses, and salt to the women. According to the newspaper Carolina Watchman, the agent at the railroad depot insisted he had no flour. The women broke into the depot, took ten barrels of flour, and left the agent “sitting on a log blowing like a March wind.”

Shortages in the western county of Madison had a more tragic result. A group of Union sympathizers from Shelton Laurel raided the town of Madison for supplies. In retaliation for the looting and for attacks on Confederate soldiers, Brigadier General Henry Heth dispatched Confederate troops to the area to stop the Unionists’ raids. Lieutenant Colonel James A. Keith rounded up thirteen suspected Union sympathizers and had his men shoot them. One victim, David Shelton, was thirteen years old.

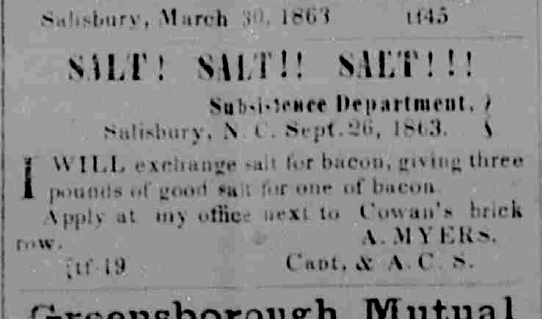

One of the things that the Unionists had hoped to get in their raid was salt. Salt was very important because people used it to preserve meat. There was no readily available substitute. By early 1863, a Raleigh newspaper reported that the price of salt had risen from twelve dollars to one hundred dollars for a two-bushel sack. Citizens depended on small private saltworks and on government-run saltworks in Saltville, Virginia, and along the coast of North Carolina. Union troops captured saltworks at Morehead City and on Currituck Sound in 1862. Throughout the war, saltworks near Wilmington produced much of the state’s supply. Workers pumped saltwater into shallow ponds, where some of the water evaporated. They then boiled the remaining water in large pans until only salt remained.

One of the things that the Unionists had hoped to get in their raid was salt. Salt was very important because people used it to preserve meat. There was no readily available substitute. By early 1863, a Raleigh newspaper reported that the price of salt had risen from twelve dollars to one hundred dollars for a two-bushel sack. Citizens depended on small private saltworks and on government-run saltworks in Saltville, Virginia, and along the coast of North Carolina. Union troops captured saltworks at Morehead City and on Currituck Sound in 1862. Throughout the war, saltworks near Wilmington produced much of the state’s supply. Workers pumped saltwater into shallow ponds, where some of the water evaporated. They then boiled the remaining water in large pans until only salt remained.

In August 1863 the Wilmington saltworks made five thousand bushels of salt. David G. Worth, the state’s salt commissioner, wrote the next month to Governor Vance that production was below normal because many of the workers were sick with a “malignant fever” and because of other struggles, including getting firewood.

Many people employed at the Wilmington saltworks worked there because they objected to serving in the army for religious or personal reasons. That worried Major General William Whiting, the Confederate commander of the area. He thought the war objectors would act as spies or send signals to Union ships off the coast. Whiting also wanted more workers for building forts to protect the city. At one point, his fears led him to seize all of the horses, workers, and boats belonging to the saltworks. The governor wrote, “This is a great calamity to our people, to stop the making of 350 bushels of Salt per day right in the midst of the pork packing season . . . [the salt works] is almost as important to the State, as the safety of the city, as our people cannot live without the Salt.” In spite of the need for the saltworks, Whiting closed it for good in late 1864 and made the workers labor on a fort. The Union army and navy were threatening to attack Wilmington. The city was very important for the Confederates. It was the last open port where ships could bring in supplies.

After the Confederates surrendered in April 1865, North Carolinians could return to their farms and import some things they needed from outside the state. Life was very different when the war ended. Formerly enslaved people became free to work for themselves. More than forty thousand of the state’s men had been killed, and many others had been wounded. A lot of property had been destroyed. It took time, but eventually North Carolinians were able to grow and buy food again, perhaps appreciating it more after suffering wartime shortages.

At the time of this article’s publication, Thomas Vincent was an assistant correspondence archivist at the State Archives, part of the North Carolina Office of Archives and History. He holds a master’s degree in public history.

Resources

Civil War food in libraries [via WorldCat].

Image credits

Battle of Bentonville reenactment. Civil War campfire. North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources.

Advertisement for salt from the November 30, 1863 issue of the Carolina Watchman, a weekly and semi weekly newspaper from Salisbury, North Carolina. From the North Carolina State Archives' digital collection NC Newspapers.

1 January 2009 | Vincent, Thomas