By Timothy N. Osment

William Holland Thomas, state legislator and “white chief” of the Cherokee, was 56 years old when the Civil War began. From the beginning of the war, he openly promoted the idea of North Carolina Cherokee fighting for the Confederacy. In 1862 he convinced Confederate authorities to allow him to raise a regiment of Cherokee and white soldiers to act as a guerrilla force for local defense. The regiment of mounted volunteers was known as the 1st Regiment, Thomas Legion, and averaged about 1500 men. The Legion’s unique blend of Cherokee and white mountaineers spent much of the war in western North Carolina preventing Union forces in East Tennessee from entering the Tar Heel State. They defended the mountain region from “bushwhackers" and deserters, but they also fought with Jubal Early in the Shenandoah campaign in 1864. In the last months of the War, Thomas returned to North Carolina to recruit an additional Cherokee battalion. Thomas's men remained loyal to him throughout the war and fought until the end. The Legion participated in the last skirmish of the war in North Carolina before surrendering at Waynesville in May 1865. The strain of active military service took a toll on Thomas’s physical and mental health. Adding to the stress were his responsibilities as leader of the North Carolina Cherokee.

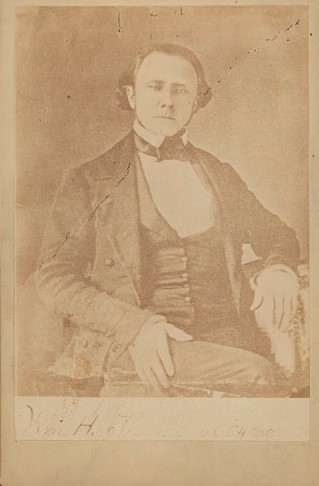

From his birth in 1805 to his death in 1893, William Holland Thomas led an exceptional life. Born in Haywood County in western North Carolina, he was apprenticed to a store owner who lived west of the Balsam Range near the Cherokee Nation. In his teens, Thomas learned the Cherokee language, taught himself to read law, and upon the death of his benefactor assumed operation of their small trading post. Befriended by the Cherokee Chief Yonaguska, Thomas was given the native name Wil Usdi (Little Will) and became chief of the tribe upon Yonaguska’s death. Thomas guided the Cherokee that remained in Western North Carolina after a majority of the tribe was forcibly moved to Oklahoma in 1838. He used his legal knowledge and status as chief to ensure that the Cherokee regained control over a portion of their land and were allowed to maintain a degree of autonomy. Additionally, he grew his commercial interests and served as a Democratic state legislator from 1848 until the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. When the war began, Thomas joined the Confederate cause and called for the South’s secession. He organized a notable military unit, including in its ranks both Cherokee and white recruits – an uncommon and controversial combination. This militia is known in history as the Thomas Legion.

Tensions between the North and South finally erupted into war in April, 1861. At the time, William Holland Thomas was serving in Raleigh representing his home district, the lands around and including the Cherokee Nation in western North Carolina. When it became evident that the war would escalate into a national civil war, Thomas left the state capital and, at age 56, prepared to aid the Confederacy. Arriving back home, he initially raised a company of 200 Cherokee that called themselves the Junaluska Zouaves. Later in the year Thomas convinced Confederate authorities that it would be worthwhile to enlist Cherokees into the regular army for local defense. By April 1862 he had raised a company that was initially designated the North Carolina Cherokee Battalion.

Company elections were held and Thomas was elected captain and then promoted in rank to major. The battalion served as a home guard for East Tennessee and western North Carolina. Primarily responsible for guarding railroad bridges and mountain passes, the Cherokee Battalion was soon ordered into Tennessee. Upon arrival, Thomas petitioned his superiors to authorize the raising of additional "Indians and whites as I may select." His request was approved, and by the summer of 1862 he had assembled a regiment of five companies of which three were white and two Cherokee. He also formed an additional battalion of two white companies under separate command. Local mountain folk referred to the units as the “Highland Rangers” or “Thomas’s Legion of Indians and Highlanders.” In September 1862, Thomas was elected colonel of the entire regiment now officially recognized as the First Regiment, Thomas Legion. By this time there were well over 1,000 men divided into ten companies, eight white and two Cherokee. Other units of the Legion, under separate command, included three cavalry companies, five infantry companies, one artillery company, and one company of “miners and sappers.” The whole force averaged between 1,500 and 2,000 men throughout most of the Civil War.

A contingent of the Legion was ordered into East Tennessee in late 1862, including two Cherokee companies. There an unexpected cultural conflict between Indians and whites occurred. After suffering an ambush by federal soldiers, one of the Cherokee companies counterattacked. They were successful but their leader, a full-blooded Cherokee, was mortally wounded. Incensed at the loss of their comrade, members of the company scalped several wounded or dead Union soldiers. Thomas had worked his whole life to overcome white prejudice and stereotypes directed towards Indians – and he knew this action by his troops could explode into a racial melee. He quickly rushed to control the incident and returned the scalps to the Union camp for proper burial. Disaster was averted. In fact, the Cherokee and the Thomas Legion eventually became recognized as one of the most courageous and honorable units that the Confederacy fielded.

For more than a year the Thomas Legion fought in various capacities throughout East Tennessee and across the state line in North Carolina, primarily in Madison County. Often Thomas found himself battling his superiors to maintain control of his unit within the confusing, fluctuating command structure that plagued the Confederacy. On several occasions the situation got so bad that he was arrested. Once he was charged with “disobedience of orders” and another time with “harboring deserters.” Each time Thomas escaped serious prosecution only through the intervention of outside authority and the Confederacy’s desperate need for manpower.

Thomas believed his Legion was being used ineffectively and petitioned his superiors to return them to North Carolina under his full command for the purpose of local defense. After months of urging his request was granted. However, that order was reversed before it could be implemented. The Legion was ordered to the Shenandoah Valley to join Confederate forces struggling to repel Union invaders.

The ravages of the war were taking their toll on the Thomas Legion. It was only 500 strong when it joined the fighting in Virginia. Early setbacks for the Confederacy soon reversed, and eventually the Shenandoah was recaptured from the Union. However, the Legion was suffering mounting casualties and its size continued to shrink. When Thomas finally received orders to return to North Carolina, he commanded fewer than one hundred men. However, after Shenandoah, the Legion’s worth was evident in a statement issued by Confederate General Gabriel C. Wharton: "The gallant conduct of your command rendered your efforts to rejoin your command in North Carolina abortive, and the constant refusal to your many applications for transfer is complimentary evidence of the esteem in which you were held, and a grateful acknowledgement of the services you could render."

That was certainly not the first or last time the Thomas Legion was recognized. In 1863 the Knoxville Register wrote, "an Indian [from Thomas's Legion] always executes an order with religious fidelity. They scrupulously respect private property -- there are no reports of depredations where they are encamped. They are the best scouts in the world" After one successful campaign the men of the Legion received a letter from the commanding general stating, "Such exhibition of valor and soldierly bearing will receive, as it deserves, the ever lasting remembrance of a grateful Country and ever be an object of pride to their General."

Returning to North Carolina, the war was not over for the Legion. Thomas was ordered to raise additional troops, and by April 1, 1865, the Legion numbered 1,200 of whom 400 were Cherokee. However, they were too late to save the Confederacy. Robert E. Lee surrendered eight days later at Appomattox. Positioned in the mountains surrounding William Thomas’s hometown of Waynesville, the Legion officially surrendered on May 9, 1865. Even their surrender has become legendary. Thomas and two other officers marched out of the hills to discuss terms with Union Colonel W. C. Bartlett. They were escorted by “twenty of the biggest Cherokees” Thomas could round up. Bartlett was so impressed by the Confederate leaders and their escort that he allowed the Legion to keep their arms and equipment and let Thomas know that he, Bartlett, and his troops, would soon leave the area.

Thomas and his men were the last Confederate soldiers to surrender in North Carolina. Much has been written about their spirit and bravery. Their sacrifice and contribution to a cause in which they believed is truly remarkable. As a part of the pride and heritage of the mountains, the Thomas Legion emerges as a bright beacon along a historical trail that for Native Americans was often blocked by carnage, desperation, and tears.

The drama "Unto These Hills," performed every year, is a wonderful account of the struggles endured and overcome by the Eastern Band of the Cherokee, William Holland Thomas, and others.

Source Citation:

Osment, Timothy N. "Thomas Legion." The Digital Heritage Project. https://aip-arts.org