Thomas Wolfe is considered one of the most noticeably autobiographical novelists in American literature. Strongly influenced by his hometown of Asheville, its citizens and by the boardinghouse, “Old Kentucky Home” owned by his mother, Wolfe turned to his childhood for inspiration for his writing. During his career, Wolfe produced four novels — Look Homeward, Angel, Of Time and the River, The Web and the Rock, and You Can't Go Home Again — as well as numerous short stories, novellas, and plays. With his experiments of new forms, language, and ideas, Wolfe helped shape modern American literature.

Early years in Asheville

The youngest of eight children, Thomas Wolfe was born in 1900 to William Oliver (W.O.) and Julia Wolfe. A stonecutter with a shop in downtown Asheville, N.C., W.O. made a profitable living carving tombstones and monuments. Julia worked tirelessly as a school teacher and a book seller before she was married. After her marriage to W.O., Julia’s desire to work did not subside. Julia began to accept boarders to stay in their home. With her earning she began her real estate speculating. She saw investments in land and real estate was the way to solidify her fortune. Hoping to cash in on Asheville’s tourist trade, Julia purchased a boardinghouse just two blocks from where the family lived. In order to properly run her business, Julia moved from the family home on Woodfin St. and into the boardinghouse called "Old Kentucky Home." Julia brought just one of her children to live with her in the boardinghouse, Tom. Just six years old at the age of this move, Tom’s life became anything but normal.

Known for being a tourist destination and a health resort, Asheville boomed in the early twentieth century. The city listed over one hundred boardinghouses during this time. During the busy summer months, Julia could hold over thirty boarders in her business. Charging a dollar a day for each boarder, she provided two meals and a place to sleep. Tom, although he lived with his mother in the boardinghouse, never had a room or even a bed, to call his own. His mother shuffled him from room to room depending on availability of beds. If no space was available in the boardinghouse Tom would be sent to the family home to spend the night with his father and siblings. This move to his mother’s boardinghouse “marked a recognition that the turbulent disorganization of his family was not some transient phase but a permanent condition."1 He desired his family to be under one roof, and would later even refer to himself as a vagabond growing up, having two roofs, but no true home.

Thomas Wolfe spent most of his young life attempting to find normalcy. He found respite in the library where he read for hours. Tom devoured the writings of Sir Walter Scott, Charles Dickens and Herman Melville. Tom desired to accompany his older siblings and go to school. The first time Tom went to school he had to sneak away from his mother’s watchful eye and followed his brother. Although Julia believed Tom to be too young to start school, his teacher decided to keep him in the class. School allowed a place for Tom to excel and he did especially so in his writing.

A young writer

By 1912 Tom’s writing ability became apparent and he was accepted to a private high school, The North State Fitting School. The school, started by his former principle and his wife, John and Margaret Roberts, led Tom to put education and his studies at the center of his life. He studied German, Latin, Greek, English, history and mathematics, but it was his study of literature with Mrs. Margret Roberts that he loved best.

The Roberts, especially his instructor, Mrs. Roberts, encouraged and nurtured Tom’s love of writing and encouraged him to further his education even when his family discouraged him going to college. Tom contributes much of his success and education to the Roberts. He had become close to the couple through his school years and when his first novel was published, Tom sent Margaret an autographed copy calling her “the mother of my spirit."2 The affection he felt for her was the first of several attachments he formed with older, influential people. Tom and Mrs. Roberts kept in contact throughout the years.

Tom graduated from the North State Fitting School in 1916 with the highest literary honors and was now ready to leave Asheville. Just 15 years old, Tom left his hometown to attend the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. By his sophomore year, Tom began to achieve recognition as a writer with one of his poems being published in The University of North Carolina Magazine. As Tom began to settle into college life, tragedy struck. At the beginning of his junior year, his brother Ben, who looked after Tom most of his life, died at the age of twenty-six.

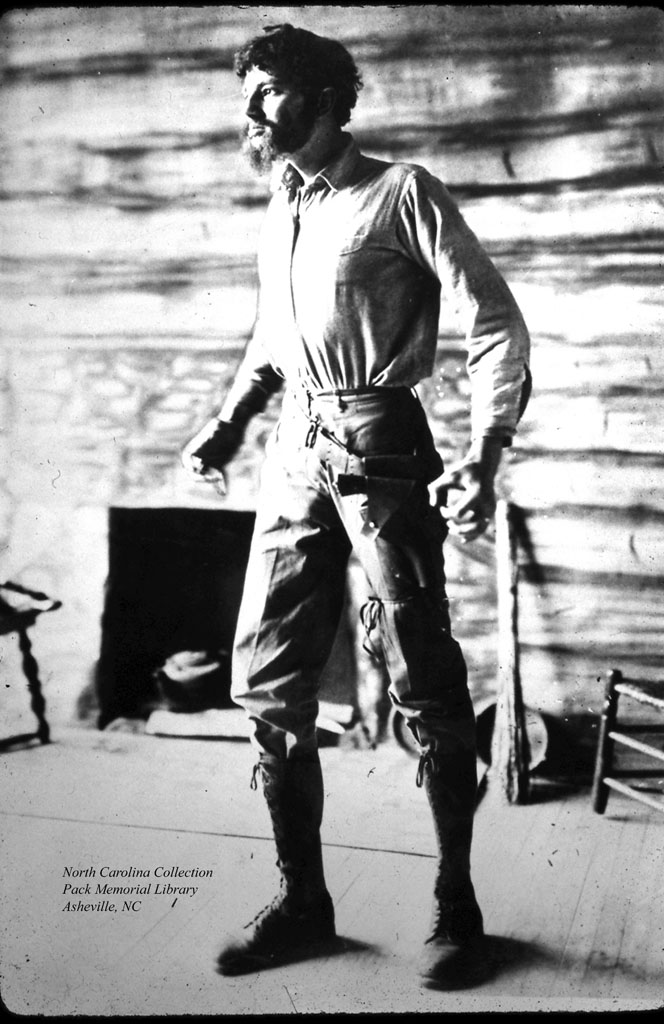

After Ben’s funeral Tom returned to Chapel Hill and focused on his writing. He joined the Carolina Playmakers, a course in playwriting taught by Fredrick H. Koch. Koch encouraged his students to write ‘folk plays’. Wolfe interpreted this as “plays that came ‘from the soil’ and depicted people and places within the writer’s own experience."3 Tom’s first play, entitled The Return of Buck Gavin, was the first to be produced by the Playmakers and starred Tom in the lead role. Tom dreamed of becoming a famous playwright.

After graduating from UNC in 1920, Wolfe decided to continue his education by attending Harvard and study playwriting under George Pierce Baker in his famous ’47 Workshop. Wolfe threw himself wholly into writing plays with Baker’s guidance. After three years at Harvard, Wolfe graduated and his play Welcome to Our City was staged. The play lasted just over four hours. The play was “the most ambitious thing-in size the Workshop has ever attempted, there are ten scenes, over thirty people, and seven changes of setting,” Tom wrote his mother.4 Welcome to Our City was not a success.

Tom submitted Welcome to Our City to the Theatre Guild, but the play was declined, so he began looking for work. He found it in February 1924 teaching English at Washington Square College in New York. Tom had little time for creative writing. He decided to travel to Europe after he taught his summer term. On October 25 Wolfe began the first of seven trips to Europe. By June 1925, motivated by lack of money, Tom decided to return to his teaching position in New York. He left Europe in late August for America. It was during this return trip Tom met the woman who would be the greatest love of his life, Aline Bernstein.

Aline Bernstein was nineteen years older than Tom and married. Aline had achieved great success in the area that Tom could not, the theatre. Her father was a famous actor and Aline had grown up in the heart of the New York theatre district and developed a career designing costumes and sets for the Neighborhood Playhouse. By January 1926, Aline and Tom began to share an apartment. They would spend most evenings together before Aline would return to her house and family at night. Aline encouraged Tom to move from writing plays to novels.

Look Homeward, Angel

With this encouragement, Wolfe began to write an autobiographical novel while on a trip to Europe in June, 1926. He filled 17 ledgers of writing while on this trip, but the novel was not done. It took him another trip to Europe in July 1927 and a few more months of work before his manuscript was done. Finally on March 31, 1928, he completed the manuscript now titled O Lost.

O Lost did not fit neatly into any literary category. The novel, totaling 1,114 pages with 330,000 words, was about three times longer than the average novel. Its mere size made it difficult to find a publisher. Discouraged, Tom took his fourth trip overseas and in October 1928, received a letter from Maxwell Perkins, legendary editor at Charles Scribner’s Sons Publishing, regarding O Lost. He stated, “I do not know whether it would be possible to work out a plan by which it might be worked into a form publishable by us, but I do know that… it is a very remarkable thing, and that no editor could read it without being exemd by it and filled with admiration."5

Tom returned from his voyage to meet Perkins in January 1929. Many months were dedicated to the editing of Wolfe’s novel. Perkins felt that it lacked form and fluidity. According to Perkins, even the name O Lost needed to be changed. Perkins also began to realize through the editing process the heavily autobiographical nature of the novel. He warned Wolfe of a backlash from his hometown.

With this concern in mind, Wolfe made a short visit to Asheville in September 1929. Although he wrote Perkins, “my family knows what it’s all about,” Wolfe talked little of his forthcoming book.6 Few were prepared on October 18, 1929 for what they would read in Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel. The initial exemment of a hometown author wore off quickly when the townspeople realized they were the basis of Wolfe’s colorful characters.

Positive reviews from around the world came in favor of Wolfe’s novel, but in his home town of Asheville, he became a hated man. The local paper, The Asheville Times, reviewed the book two days after its publication. It warned, “[Asheville citizens] will read it because it is a story told with bitterness and without compassion, of many Asheville people."7

Exile from Asheville

Worried about the strong reaction and disapproval from his hometown, Wolfe did not return to Asheville for almost eight years. During these years of exile Wolfe traveled over seas, lived in various apartments and hotels throughout New York City, and worked feverishly on his writings. In 1935 Wolfe published his second novel, Of Time and the River. Wolfe’s second novel was well received. After this second novel, Wolfe left Max Perkins and Scribner’s publishing for Harper & Brothers and chose Edward C. Aswell as his new editor.

Wanting a rest from New York and a chance to focus on his writing, Thomas Wolfe finally came home in 1937. He spent the summer staying between the boardinghouse with his mother and a cabin outside of town. Tom was now seen as a local celebrity. His novels were well received throughout the world and had helped Asheville through the hard times of the Great Depression by increasing tourism to his hometown. Due to his popularity, Tom found little time for writing and returned to New York City.

In the spring of 1938, Wolfe was asked to speak at a literary banquet at Purdue University. After his talk, Wolfe decided to continue his trip out west and was asked to give a writers perspective of the eleven new national parks. Wolfe joined two men from Oregon for the two week tour. Shortly after this trip, he developed pneumonia, which progressed into tubercular meningitis. Wolfe died on September 15, 1938, just eighteen days short of his 38th birthday. He was buried in Riverside Cemetery in Asheville.

It was after his death his last two novels were published. When Wolfe died, he left a huge manuscript on which he had worked for so many years. It is from this large manuscript his last two novels were formed. The Web and the Rock (1939) and You Can’t Go Home Again (1940), were heavily shaped by his editor Edward Aswell.

Thomas Wolfe remains one of Asheville’s most renowned literary figures and continues to influence writers today. A member of the first generation of American contemporary authors, Wolfe experimented with new forms, language, and ideas. Thomas Wolfe’s legacy as a gifted writer and storyteller, helped in shaping modern American literature.

- 1. David Herbert Donald, Look Homeward: A Life of Thomas Wolfe (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1987), 11.

- 2. Ted Mitchell, ed., Windows of the Heart: The Correspondence of Thomas Wolfe and Margaret Roberts (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2007), 121.

- 3. Herbert, Look Homeward, 56.

- 4. John Skally Terry, ed., The Letters of Thomas Wolfe to His Mother (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1946), 45.

- 5. John Hall Wheelock, ed., Editor to Author: The Letters of Maxwell E. Perkins (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1979), 61.

- 6. Elizabeth Nowell, ed., The Letters of Thomas Wolfe (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1956), 203.

- 7. Walter S. Adams, “Amazing New Novel is Realistic Story of Asheville People.” The Asheville Times, 20 October 1929, p. 1.